Fortress of Louisbourg: from History to Historic Site

par Johnston, A.J.B.

Standing on a low-lying peninsula along the north-eastern shore of Cape Breton Island, the Fortress of Louisbourg seems to rise right out of the sea when approaching by water. Coming by land along Route 22 from Sydney this picturesque complex of fifty or so buildings that appear to have survived from another era is equally impressive. Once close enough to make out the details, visitors see that the ensemble is nearly surrounded by fortifications, an 18th-century set-piece that looks as if it has been there for centuries. It hasn't, of course. For this is the Fortress of Louisbourg, a fortified town-site that is a one-fifth reconstruction of what had once stood on that very spot: the 250-buildings ville fortifiée erected by French colonists between 1713 and 1745. The goals of the ambitious Canadian reconstruction project of the second half of the 20th century, built between 1961 and 1982, were to create a major cultural tourism attraction in Atlantic Canada and to encourage interest and pride in a then little-known part of Canadian history.

Article disponible en français : Forteresse de Louisbourg : un rendez-vous avec l’Histoire

A Heritage Site Laden with History

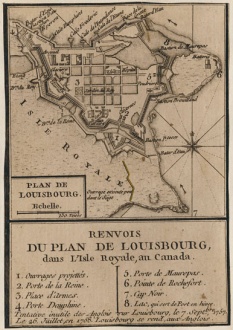

The end result is the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site, a 10-acre reconstruction zone surrounded by 1.17 km [roughly ¾ of a mile] of fortifications (a quarter of the original total), which in turn is set within a protected area of nearly 60 square kilometres [23 square miles]. In total, the Fortress is one of the largest national historic sites in the country. The largely forested area beyond the reconstructed 18th-century town-site is much more than a buffer; it has tremendous heritage value all its own. Beyond the rebuilt walls of the fortress are found the archaeological vestiges of French settlement areas and defensive positions; the remains of Canada's first lighthouse; the beaches where attackers came ashore in 1745 and 1758; and what remains of the many siege camps and batteries erected by New England forces in 1745 and British forces in 1758. Though the official name given to the entire protected heritage area is the Fortress of Louisbourg, that is a 20th-century designation. In its 18th-century heyday the town and port and surrounding hinterland was known to the French who lived there and to the administration at Versailles that valued it so highly simply as Louisbourg, or Port de Louisbourg, or Ville de Louisbourg.

The Fortress became a Canadian national historic site in 1928, decades before any reconstruction would be undertaken. Initially only a small portion of what is now protected was set aside. The focus was on the town-site and lighthouse location and it was preceded by a wave of land expropriations and building removals. In 1935-36 the Canadian government constructed a masonry museum, a building that still stands today. For a quarter century it presented the history of Louisbourg through artefacts, maps, documents, portraits and a large model. Only when the government decided in the 1960s to research and rebuild an entire section of the historic site was the museum rendered redundant, though in the 1980s it would be refurbished as an exhibit area telling the story of Louisbourg after the departure of the French up to the time of the reconstruction era. A second wave of expropriations and building removals took place along the north shore of Louisbourg harbour and at Kennington Cove during the 1960s, to make way for a range of new services and because historic site aesthetics of the period called for removing what were thought of as "modern intrusions".

The "Real" Louisbourg

In its original 18th-century manifestation, Louisbourg was an assertion of France's determination to retain its economic and strategic interests in Atlantic Canada. The primary desire was to retain a base for the lucrative cod fishery after Newfoundland was ceded to Great Britain by the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). The overall North Atlantic fishery was far more valuable to France than the fur trade ever was, whether as a source of direct profits or as an invaluable nursery of seamen for the navy. In Louisbourg's case, the port was not just the centre for cod exports to France but also a pivot or transhipment port in a triangular trading system that involved France, the Antilles, and Canada. Voltaire himself described the Cape Breton colony as "the key" to France's possessions in North America, because of its impact on the maritime economy of the mother country.

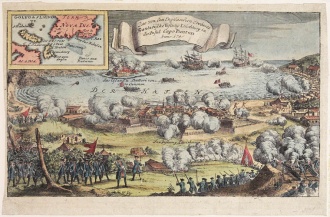

To the British and the Anglo-Americans on the other hand, the Louisbourg that developed between 1713 and the 1740s loomed as a threat, for economic, military and naval reasons. To the mercantilist thinking of the era, Louisbourg's maritime prosperity (with an average of 150 vessels sailing in and out of the port each year) meant that it was taking away codfish and trading wealth from the Anglo-American colonists. Compounding the situation were the European-style masonry fortifications the French erected at Louisbourg between 1720 and 1745. That was an approach rarely found in North America where the usual defences were blockhouses and earthworks. As a result, the French stronghold on the shoreline of Cape Breton Island loomed large in British and Anglo-American thinking. Benjamin Franklin, for instance, wrote on the eve of the 1745 New England attack on Louisbourg that the Cape Breton fortress was a "tough nut to crack". Once captured (in fact it was captured twice, both in 1745 and 1758), Louisbourg ceased to be a symbol of the French presence in Atlantic Canada. Instead it became a symbol of how British men-at-arms and emerging superiority of the Royal Navy on the high seas had prevailed in the long Anglo-French imperial rivalry in the Americas.

Reconstructing Louisbourg on the Ruins of the Past

With the reconstruction of the Fortress of Louisbourg in the mid-20th century, the earlier symbolic associations became less important. The Government of Canada's decision to rebuild an entire corner of the long-vanished French colonial town as a sort of "Williamsburg North" gave the Fortress of Louisbourg a new significance as the country's most ambitious example of a then popular way of dealing with heritage: that of reconstructing a representative sample so that the public can experience what is often described as "living history". The term meant using costumed interpreters within buildings and exterior spaces that are furnished to give the appearance of a bygone historical period. In the case of the Fortress of Louisbourg, the period selected for the interpretation program was the summer of 1744, just before the town first felt the damaging effects of bombardment and defeat. Yet the Fortress staff never limited themselves to an exclusive "living history" approach. The Parks Canada administered site also uses didactic exhibits, models, films and guided tours to communicate aspects of the site's complex history that are difficult or impossible to talk about with a focus on 1744.

It is worth noting that the Louisbourg of the 18th century included not just what today falls within the boundaries of the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site. Historical Louisbourg included the entire shoreline stretching around the kidney-shaped harbour, including what today is the modern community of Louisbourg. The compartmentalization of that once unified settlement area into two main parts-one part located in a lived-in modern municipality and the other on a historic site set aside for public education and enjoyment-did not happen overnight. Soon after the second and final capture of Louisbourg in 1758, the British rounded up and shipped off every French soldier and civilian they could; the combatants went to Britain and the civilians to France. The forced relocation involved perhaps as many as 10,000 people, because there were nearly a dozen other French communities on Île Royale (Cape Breton Island) affected as well. Two years later, in 1760, Britain's Prime Minister William Pitt ordered the systematic demolition of all Louisbourg's fortifications just in case the place was again handed back to France. (That didn't happen, for when the treaty process to end the Seven Years' War concluded, of all that had once been New France, only the islands of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon were retained as French possessions.) A British garrison stayed at Louisbourg until 1768, without rebuilding the masonry fortifications yet still living in the town that had been severely damaged during the bombardment of 1758. When the soldiers finally pulled out, so did the majority of the community of several hundred British, Irish and Anglo-American civilians that had grown up after the conquest.

In the decades that followed, a small civilian community continued to live in the area of what had once been the French intra muros of Louisbourg, though they numbered in the dozens where the French population had once reached nearly three thousand. Over the course of the 19th century a new Louisburg began to grow (spelled without the second "o" until it was re-inserted in the 1960s). The new community that began to take shape was located increasingly across the harbour from the low-lying peninsula where the ville fortifiée had once stood. And so the town continues today, the houses, businesses, etc of the modern Louisbourg being primarily established along what the French in the 18th century called the côte nord.

The Heritage Appropriation of Louisbourg; a Question of Ownership

As far as commemorating the 18th-century occupation of the area and associated events of military significance, the British garrison put up a makeshift stone marker to what they had accomplished in capturing the place just before they withdrew in 1768. The next monument was erected in 1895 when a private American organization (General Society of Colonial Wars) erected a tall column in the area of the site's most prominent ruins, in what had once been the Bastion du Roi [Royal Fortress]. The occasion was the 150th anniversary of the New Englanders' victory in 1745. The commemoration drew protests from Acadian Senator Pascal Poirier and other groups in Canada, who contended that the federal government should not allow foreigners to come into the country to erect monuments to what French Canadians regarded as a defeat. Prime Minister Mackenzie Bowell replied that it was a private society putting up a monument on private land; the government had no role in regulating such matters.

And so it remained until 1919, when the federal government created an arms-length advisory body (Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada - Commission des lieux et monuments du Canada) to give advice on matters of historical commemorations. One of the first sites considered for commemoration at the initial 1919 meeting was Louisbourg. Neverthless, it was not made an official national historic site until 1928, after the initial project of land expropriations was over. At the time, the bygone intra muros of Louisbourg consisted of mounds of rubble and earth with a couple of dozen modest wooden houses, fence lines and grazing animals.

In the 1930s and 1940s a number of non-governmental organizations (religious orders and others) put up additional monuments at Louisbourg, within what had become a national historic site. All those monuments are still there, though in the case of the tall column of the General Society of Colonial Wars, it was relocated to Rochefort Point during the early 1960s to make way for the reconstruction of the Bastion du Roi. It was damaged in the move and is now only a little more than half its original height.

A Precarious Heritage Site

That the Fortress of Louisbourg is a multi-layered place, across time, is obvious. Less obvious, perhaps, is the challenge of its very setting, the low-lying peninsula on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. It is a spectacular setting that offers a strong and vivid sense of place. Yet there is an ominous part to the setting because sea level at Louisbourg today is already at least a meter higher than it was in the mid-18th century. The rise in sea level has been going on for thousands of years - 5000 years ago what is now the harbour at Louisbourg was an inland lake - and there are predictions that the Atlantic could rise another meter over the next hundred years. Already, during certain storms when winds combine with a rising tide there are huge surges, which on occasion have flooded and damaged a few areas of the Fortress reconstruction and nearby Rochefort Point. Might it be that the sea and coastal location that was crucial to Louisbourg's 18th-century prosperity and significance will lead to the gradual subsidence and eventual disappearance of an important national historic site? It's a question that must be asked of many coastal historic sites, with the Fortress of Louisbourg in the vanguard.

A.J.B. Johnston

Independent Historian

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Aux capitaines et aut

Aux capitaines et aut

res officiers e... -

Côte du Cap-Breton, p

Côte du Cap-Breton, p

rès de Louisbou... -

Forteresse de Louisbo

Forteresse de Louisbo

urg - Parc hist... -

Forteresse de Louisbo

Forteresse de Louisbo

urg - Parc hist...

-

Forteresse de Louisbo

Forteresse de Louisbo

urg (Nouvelle-E... -

Forteresse de Louisbo

Forteresse de Louisbo

urg, Île du Ca... -

Forteresse de Louisbo

Forteresse de Louisbo

urg, Île du Ca... -

Joueurs de cornemuse

Joueurs de cornemuse

sur les rampart...

-

L'expédition contre

L'expédition contre

le Cap-Breton (... -

Les ruines de la fort

Les ruines de la fort

eresse de Louis... -

Monument Louisbourg,

Monument Louisbourg,

N.-É., 1901 -

Parc historique natio

Parc historique natio

nal de la Forte...

-

Parc historique natio

Parc historique natio

nal de la Forte... -

Parc historique natio

Parc historique natio

nal de la Forte... -

Parc historique natio

Parc historique natio

nal de la Forte... -

Plan de Louisbourg en

Plan de Louisbourg en

1765

-

Plan du port et de la

Plan du port et de la

ville de Louis... -

Plaque datant de 1731

Plaque datant de 1731

, retrouvée lor... -

Prise de Louisbourg p

Prise de Louisbourg p

ar les Anglais,... -

Régiments royaux - O

Régiments royaux - O

fficier du Rég...

-

Rue de Louisbourg, 20

Rue de Louisbourg, 20

06 -

Ruines du fort, Louis

Ruines du fort, Louis

bourg, Cap-Bret... -

Ruines du vieux fort

Ruines du vieux fort

français, Loui... -

Sir Jeffrey Amherst

Sir Jeffrey Amherst

-

Timbre de la Forteres

Timbre de la Forteres

se de Louisbour... -

Vue aérienne. Restaur

Vue aérienne. Restaur

ation de la for... -

Vue de Louisbourg en

Vue de Louisbourg en

Amérique du No... -

Vue de Louisburg [Lou

Vue de Louisburg [Lou

isbourg], dans ...